-

contact info:

mjsersch@gundersenhealth.org

-

Review of Demons book by Todd Hayes (originally in International Journal of Religions and Traditions: https://regressionjournal.org/book_review/demons-on-the-couch-spirit-possession-exorcisms-and-the-dsm-v-by-michael-j-sersch/

Reviewed by Todd Hayen

in IJRT Issue 31, 2020Michael J. Sersch’s Demons on the Couch: Spirit Possession, Exorcisms and the DSM-5 is an immaculately researched and referenced treatise on possession and exorcism presented through the lens of modern psychotherapy and the DSM-5 (the diagnostic bible of the mental health field.)

Sersch states in his introduction:

In writing this book, I hope to answer why demonic possession has held a cultural fascination for over two millennia as well as how clinicians can successfully and ethically deal with patients who legitimately believe they are possessed by a spiritual force. There is also mounting evidence that integrating a patient/client’s worldview into clinical practice, including their spirituality and faith practices, increases their likelihood of getting better (Lund, 2014) which is a position I am overtly advocating. (p. 5)

He also claims that he has no desire to attempt to prove or disprove spirit or demonic possession (p. 5). His approach is largely clinical and pedagogical: what does a clinician do with a patient who claims they are possessed?

Sersch divides his thesis into three sections, each section dealing with a different aspect of possession and exorcism. The first section, appropriately enough, deals with the history of spirit possession, demon possession, and different forms of exorcism. The second section is more clinical in its approach going into detail on such topics as the different designations for diagnoses found in the various editions of the Diagnostic Statistical Manual (DSM) such as Multiple Personality Disorder (an older label having been replaced with Dissociate Identity Disorder in the fourth edition of the DSM (APA, 1994)). The third section focuses on suggestions for the clinician, again: how does the clinician handle patients claiming to be possessed?

Sersch’s book is an excellent resource. It is quite academically robust and includes a solid reference for nearly every sentence. It has close 20 pages of references. For a book of only 141 pages of text, that is quite an accomplishment. Sersch claims this book was originally a thesis for the his Master’s degree and was subsequently expanded into a more accessible read—although at times this reader still got the impression he was reading a doctoral dissertation literature review. That being said, however, the author has made it a point to interject his own personal insights from time to time in the first person, and although a bit jarring after reading pages of academic text, it allows for a more intimate approach. I found myself wanting to hear more of Sersch’s personal insight.

Section 1

Sersch begins his section of the history of possession and exorcism with a basic definition: “Possession is defined as a trance state that includes the loss of the individual’s persona and social identity, which is replaced by an alien entity, usually spiritual or at least non-human” (pg.10). He also makes it clear that possessions can be found in objects as well as living things. Through very careful referencing of other studies and literature, Sersch makes the argument that possession, as defined by the above definition, is to be found in nearly every culture and personally believed, even today, by a very large number of people (see the text for quantifications of these statements, they vary depending on the study and when the study was conducted.)In this section Sersch brings up an important tenet that follows the narrative throughout the book—the practitioner working with a patient who believes in possession, and believes he or she to be possessed, does not have to believe in the same manner as the patient. They only need to understand “that it is meaningful for the patient” (p. 16). At another point in the book Sersch says: “ . . . a patient’s belief in spirit or demonic possession does not necessitate that the therapist holds the same belief, only that the practitioner respects such a belief as valid from the worldview of the patient” (p. 22). Sersch takes time in this section to examine many different cultures and how those cultures view possession, what they each bring to the phenomenon and the differing ways they approach exorcism. He also describes the primary signs of possession, first citing the Roman Catholic definition, which requires three basic criteria:

1. The possessed must speak in foreign languages or tongues,

2. They must have superhuman strength, and

3. They must know things (usually about the exorcist) that they could not possibly know.Other cultures have different criteria, some have added to these basic Roman Catholic ideas. For example, in some Islamic cultures, an indication of possession includes mental and physical illness, including the hearing of voices. Sersch is also careful to differentiate between modern medical science’s definitions of objective mental illness (or even physical illness). Although historically mental illness as well as physical illness was often considered to be caused by a possessing demon, in contemporary times exorcists are careful to rule out what the medical establishment would define as diagnosable mental illness. However, this careful scrutiny does not always find its way into an exorcism procedure, and indeed, there are practitioners who still believe that the primary causal element of mental illness is possession of some external force or entity.

Sersch also speaks at length about multiple personalities (p. 11, pp. 96-101), and how individuals diagnosed with multiple personalities can be interpreted as possessed if the alternative personality is considered to be a spirit or a demon. These can be complicated distinctions and although the definition of possession, at least as defined by the Roman Catholic church, must include attributes that are not typically found in MPD (Multiple Personality Disorder) or DID (Dissociative Personality Disorder) diagnoses, they have often been included in possession research and considered in the treatment protocols (exorcism).

As mentioned earlier, a large part of Section 1 of this book deals with the history of possession throughout the world. This is a thoroughly exhaustive survey, and again quite scholarly and well cited. Sersch points out some very interesting facts about historic possession, most notable by this reader was the view that Jesus was possessed by the Holy Spirit or the Spirit of God, in the same manner as the earlier Hebrew prophets were, an idea that was later abandoned due to it’s heretical nature. Enemies of Jesus believed he was demonic (pp. 30-31). I thought it was quite interesting as well that Chinese Daoism (300CE) used exorcism typically as a last resort to treating a person they believed was possessed. Instead they prescribed a healthy diet, proper behavior and spiritual practice (p.44). Seems like good advice treating any disease.

Sersch covers such topics as “Mass Hysteria”, “Understanding the Witch Craze”, “The Standardization of Demonology” and “The Faust Story.” He continues Section 1 with a chapter titled “Modernity and Exorcism” where he addresses modern ideas such as materialism: “ . . . one way of understanding modernity is the shift to a material world view as a majority view, away from an enchanted world influenced by spirits and spiritual forces. This definition is especially accurate for later modernity” (p. 64). He goes on to say, “Many modern thinkers automatically dismiss all reports of possession, especially in ancient literature, as an inadequate diagnosis that can better be explained now by psychological insights” (p. 65). As mentioned earlier, even recent church sanctioned exorcisms performed though the Roman Ritual (the Roman Catholic church’s manual of exorcising spirits), requires a differential diagnoses: is this a true possession, or a conventionally treated mental illness?

Spiro (1998) calls the scientific fallacy the belief that every phenomenon can be explained away in the mechanical-medical model. “There are dangers in reducing the experience of demonic possession to some supposedly more fundamental psychopathological condition, to neurosis, hysteria, psychosomatic disorder, and so forth” (Midelfort, 2005, p. 83).Increasingly, scholars are questioning the tendency to dismiss everything that is outside of our mechanicalworldview. (p. 65)

In this chapter much of Sersch’s focus is on this materialistic paradigm of modern times. Possession simply falls outside of the boundaries of the material natural world, therefore, at best it is to be ignored, at worst ridiculed, or dismissed as some other form of psychotic mental illness. Sersch meticulously visits every area pertinent to his thesis—modernity and psychology, various faiths’ exorcisms of the 20th century, popular contemporary music, and cinema. He then comments on the uprising of contemporary exorcisms, due mostly to what he calls the culture’s fear of the occult (p. 81). The popularity of Blatty’s (1971) book and movie The Exorcist undoubtedly add to this fear, or maybe their popularization was due to the fear.

Sersch then comments on exorcisms gone bad, ones where the subjects were exposed to terribly abusive interventions, such as extreme restraint, or having crosses forced into their mouths (p. 82 referring to the particular case of Michael Taylor, see Ruickbie (2015)). These are primarily cases where a differential diagnoses was ignored or never sought, which could have concluded that the proper treatment should be more conventional (the medical treatment of a diagnosed mental illness.) There have been many such “exorcisms gone bad” concentrating on physical and emotional abuse to forcibly chase out the offending demon or spirit. “Unfortunately, in many places it appears that the ancient approach of beating a person believed to be possessed in order to make the demon leave continues to be standard practice” (p. 83).When is exorcism the right choice? As mentioned before, a patient may be a candidate for an exorcism ritual if the patient believes they are possessed and they exhibit behavior that does not fit into a more conventional diagnosis. There are many elements of the practice of exorcism that hark back to a time where formal ritual was a mainstay of human experience. Again, much of this ritualistic practice in our modern materialist culture is considered passé, old fashioned, or, at worst, superstitious. However, ritual is often considered one highly effective way to practice psychotherapy. Just sitting with a client, in a sacred space, and carefully listening, and becoming empathically tuned into their suffering is a form of informal ritual. Sersch suggests that finding a good exorcist to perform the ritual of exorcism is a task that requires much attention. Monsignor Andrea Gemma is interviewed by Wilkinson (2007) and in the interview Gemma says: “So, finding someone who listens and prays is important, even psychologically. Sometimes just the fact of being listened to, or being invited into prayer and into a relationship of trust, this is a great remedy of those who are suffering” (p. 83). Sersch continues in this chapter to explore modern exorcism covering such topics as women and possession and Catholic exorcism in the 21st century.

Section 2

The first chapter (Chapter Four) in Section 2 is devoted entirely to Multiple Personality Disorder and Dissociative Identity Disorder. Here the author explains both of these disorders and their history, noting how MPD was first introduced into the Third Edition of the DSM in 1980 and was replaced by DID in the Fourth Edition. He cites this change from one of the authors of the new text who was reported as saying “the reason for the change was that patients were not suffering from multiple personalities, rather they had less than one full personality” (Loftus & Ketcham, 1994). In the revised version of the DSM-4 (TR) variants were added to the DID diagnosis—Dissociative Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (or NOS) was a person who experienced DID but the alter was a demon or spirit. DTD, Dissociative Trance Disorder and PTD, Possession Trance Disorder, was also added to the manual. These specifications opened up several therapeutic modalities as being acceptable methods to deal with the new designations.By this point in the book it becomes numbingly clear that this topic is exceptionally dense and complex and covers such a multitude of topics, diversities, histories, and anecdotal experiences it is nearly unmanageable. Again, Sersch approaches this difficulty with aplomb and confidence and thus the reader just continues to glide relatively effortlessly through it. Personally I find the topic of exceeding importance as it touches on some very fundamental truths that I believe the culture has, since the age of materialism as mentioned before, all but obliterated from the collective conscious.

We have not yet found an effective way to define, treat, or otherwise integrate, any phenomena that does not fit neatly into the materialist paradigm. Psychology and the treatment of psychological issues, is supposed to be “scientific” and that term requires adherence to laws of material cause and effect. Nowhere in psychology do we see this dichotomy of material and non-material more evident than in MPD, DID and the now accepted variants, DTD and PTD. Sersch is careful not to fall into the trap of describing these conditions in a non-scientific matter, yet makes it clear that as practitioners we have to “act” as if what our patient is describing to us is “real”. If anyone reading this has ever experienced an actual possession case and have seen, and heard, what comes from the person suffering the alleged possession, they will probably find it much easier to perceive the possession as real.

The life experience of a human being is intricately complex. The traumas a person experiences through life, both large and small, active and passive, are many and varied. If the practitioner, or patient, believes in a collective unconscious, as Carl Jung did, then the metaphysical idea that experiences expand beyond a post-natal life. Sersch makes great effort to explore various experiences that could be a key to a person who believes they have become possessed (see Chapter Six “Social Dynamics” p. 107). Life experiences, unconscious forces and agendas, cultural influences which mold a particular belief system all seem to be scientific evidence for the phenomenon of possession—at least they seem to be viable explanations.

Sersch cites Bourguignon (1976) who promoted a theory that those possessed, or claimed to be, did so as a form of role-play and that they still held a certain degree of autonomy in their execution of the possession. Sersch goes on to describe a time during his school years where he pretended to be possessed by an evil spirit. He succeeded in persuading some of his schoolmates that he was indeed possessed, but never was fully convinced himself.This story reminded me of a time in my own life when I was 13 years old and was home alone rough housing with my dog. For whatever reason I was inspired to take a paper grocery bag, cut holes in it for eyes, and draw on it, with crayons, a demonic face. I put the bag over my head and proceeded to growl, emit every horrible sound I could, while “attacking my dog” after a while I felt as if something was taking me over, and I became more and more aggressive which seemed to be out of my control. The dog became terrified and ran off before any harm could be inflicted on it, leaving me in the room writhing around on the floor in my new found demon-state. I finally got a hold of myself and pulled the bag off of my head and sat on the floor exhausted for quite some time wondering what had just happened. To this day I still wonder about it all; it was an experience I had never had, nor have had since. It does make me contemplate, and this thought is in support of some of Sersch’s commentary, that my possessed state was self-induced. Possibly with the right setting, the right ritual, and the right props, anyone can call forth an evil spirit, possibly the evil shadow that resides in all of us, only waiting for the ideal moment to be known.

Section 3

This section begins with several interviews with exorcists. Albeit of some interest it seemed to be a bit out of place. Chapter Ten is where the nitty-gritty begins—“Contemporary Treatment.” I have to admit I was a bit disappointed. I expected here an outline of an actual methodology in the treatment of a possessed patient. Sersch, continues with citing the literature and further explanations of the placebo effect, how it is important the clinician be empathic to their particular worldview, and so on. The information is sound, and useful, and of course interesting. Again, I felt a strong desire to hear what Sersch himself believed, or what his conclusions where, or if he had developed some sort of methodology.The final chapter, “Conclusion”, states in the first sentences that the new designations and their explanations in the DSM-5 (APA, 2013) give practitioners the ethical, and legal, green light to treat possession. He goes on to say that any sort of exorcism, or treatment with the same intentions as exorcism, should be performed by a qualified, ethical, and experienced practitioner—a Catholic priest, a shaman, or whomever else is considered the “expert” in the particular culture or religion or belief system. Sersch goes on to say that a person should only be referred to this treatment:

1. if the client believes themselves to be possessed and in need of an exorcism without coercion from the therapist or others,

2. they have a belief system that is consistent with belief in possession states (versus clear forms of psychosis) and most importantly,

3. the ritual is performed in a safe and respectful manner, causing no harm to the person involved. (p. 139)A very well thought out and thorough set of criteria.

In conclusion, Demons on the Couch is an excellent book. It is very well written, incredibly well cited and referenced, and contains just about everything a reader would want to know about possession through the lens of a practicing psychologist or psychotherapist. It would be accessible and useful for anyone without ruffling any feathers regarding belief or superstition as Sersch makes it evident, as he states at the beginning of the book, his intention is not to prove, or disprove the reality of possession, demons, spirits or the like.

As I stated earlier, I would have liked to have heard a bit more from Sersch himself regarding his own experiences. He tantalizes us a bit with a few anecdotal references, but it is not enough in my opinion. I also would have liked to have seen some sort of discussion about working with a possessed client without having to perform an actual exorcism, but I can understand if Sersch was intentionally avoiding that possible pit.

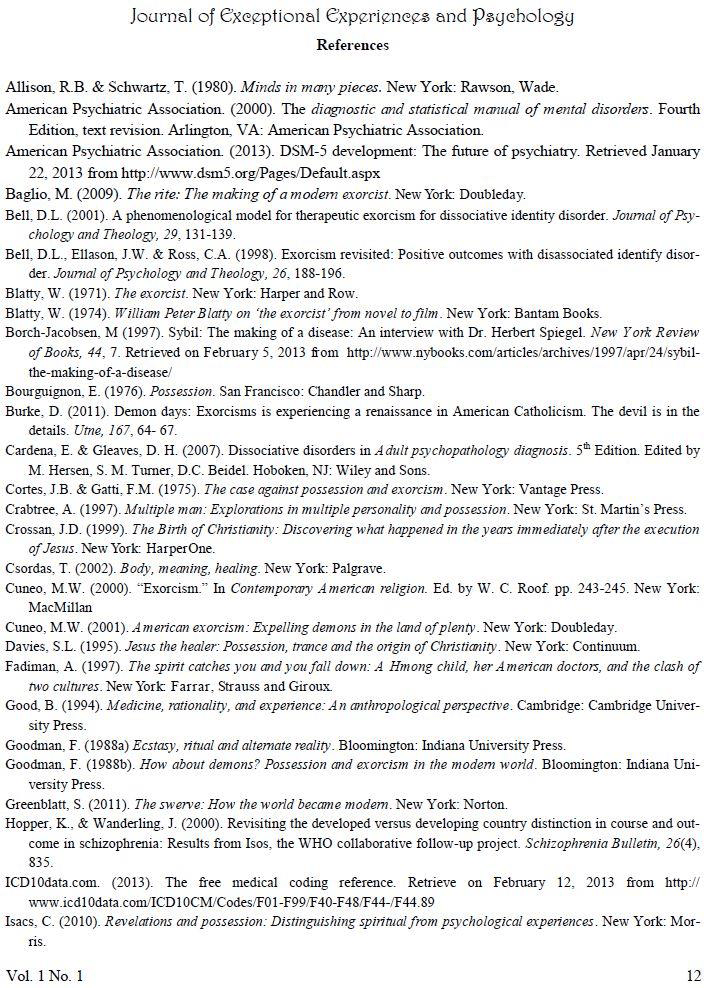

References

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). The diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Fourth Edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

—. (2013). The diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Fifth Edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

Blatty, W. P. (1971). The exorcist. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Blatty, W. P., Marshall, N. (Producers), & Friedkin, W. (Director). (1973). The exorcist [Motion Picture]. United States: Warner Bros.

Bourguignon, E. (1976). Possession. San Francisco: Chandler and Sharp.

Loftus, E., & Ketcham, K. (1994). The myth of repressed memory: False memories and allegations of sexual abuse. New York: St. Martin’s Griffith.

Lund, H. (2014). Spirituality, religion and faith in psychotherapy practice: Phenomenology and the social sciences. Ed. M. Natanson. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Midelfort, H. C. E. (2005). Exorcism and enlightenment: Johann Joseph Gassner and the demons of eighteenth-century Germany. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Ruikcbie, L. (2015). “Taylor, Michael.” In Spirit possession around the world: Possession, communion and demon expulsion across cultures. Ed. J. P. Laycock. Pp. 156-158. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO.

Sersch, M. J. (2019). Demons on the couch: Spirit possession, exorcisms and the DSM-5. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Spiro, H. (1998). The power of hope: A doctor’s perspective. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Wilkinson, T. (2007). The Vatican’s exorcists: Driving out the devil in 21st century. New York: Warner.

DEMONS ON THE COUCH: SPIRIT POSSESSION, EXORCISMS AND THE DSM-5 by Michael J. Sersch.

Cambridge Scholars Publishing; 1st Edition (February 1, 2019)

ISBN-13: 978-1527521940 -

Revisions made to upcoming Oxford Press Publication:

“Demons in the Country, Demons in the City: Conspiratorial Thinking in the Context of Possession”

Abstract:

This paper will explore three distinct possession narratives that stretch from the Greco-Roman era into the contemporary era for themes of conspiratorial thinking and the underlying anxieties that fuel these narratives. Anxiety about proper sexual behavior and appropriate gender norms, coupled with opposition to existing power structures and economic uncertainty, appear to be significant motivators for those who fixate upon conspiratorial thought, especially in the context of demonic possession and exorcisms. The oldest of these narratives explored, the suppression of the Roman Bacchanalia (Dionysiac) Rites, will be shown as having distinct parallels to the unspoken anxieties of German Catholic immigrants living in the U.S. Midwest of the 1920s, as documented in a pamphlet describing the exorcism of Anna Ecklund (aka Emma Schmid, aka Mary X). These same fears, in a contemporary setting, will be shown as motivating the participants in the attack on the US Capitol on January 6, 2021.

Keywords:

Possession, exorcism, conspiracy, Freemasons, QAnon

Introduction

Conspiratorial thinking has been particularly prominent in national and international movements as of late, fueled in part due to the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent varied health responses by government bodies. Additionally, rapid social transformation (such as technological and economic changes), coupled with changing sexual norms and gender roles, as well as economic uncertainty, undoubtedly play a factor in the appeal of conspiratorial theories. Little has been written about the overlap in conspiracy theories and possessions, even though a number of conspiracy theories allude to demonic influences. One prominent conspiracy theory, QAnon, purports that a vast underground network in systems of power (the so-called ‘deep state’), is kidnapping children to use for sexual purposes and/or to harvest organs of children (Rothschild, 2021, pp. 181-198). S. Jonathon O’Donnell (2020a, 2020b) has connected how members of QAnon attribute the motivation for such activity to demonic possession, a state that is attributed to many of their political opponents.

Historic parallels, particularly in possession narratives, do exist. The Earling Exorcism (named for the town in Iowa in which it was reported to occur) happened among the German immigrant community in the 1920s in the Midwest of the United States. A popular pamphlet narrated (a highly truncated) description of a lengthy exorcism which drew deeply on stories of Freemasons, as well as a sense of political instability and perceived threats to the religious orthodoxy of the immigrant community (Vogl, 1935, 2016, pp. 3-47). Titus Livy’s description of the Roman Senate’s suppression of the Bacchanal rituals (trans. 1936, Books 29-39) is an ancient precedent. Fear of a secret cabal continued through the Middle Ages into the modern, and now contemporary, world (see Rothschild, 2021, pp. 52-55). Religious orthodoxy does not seem to be as strong of a concern among QAnon and fellow contemporary right-wing conspiracies as is seen with both Livy and those involved in the Earling Exorcism, although anxiety over sexual norms and political stability remain repeated themes.

Several theorists will be used to help understand the connection of possession and conspiracy . David Frankfurter (2006, pp. 44-53) has emphasized the long history of attempting to form a personification of evil as a way of meaning-making. O’Donnell’s (2020a, 2020b) research into the language used by (mostly white) neo-charismatic Christians and QAnon supporters (which at times overlaps) demonstrates that belief in demonic possession as the motivating force for the supposed child rape and murder attributed to political opponents. Insights from cognitive psychology in challenging conspiratorial thinking will be explored (Elder, 2021; Lorch, 2017). Finally, creative approaches by various artists, including the Italian author Umberto Eco and the rapper Lil Nas X will be lifted up as opportunity to play with possession narratives.

The Earling Exorcism

What was once St Anthony’s Monastery in Marathon, WI is now a retreat center. This is the former home of the exorcist Theophilus Riesinger, O.F.M. Cap. A short pamphlet, Begone, Satan ([1935], 2016) was initially authored in German by Carl Vogl about the exorcisms Fr. Reisinger did with the pseudonymous Anna Ecklund in 1928, who appears to have lived in Marathon for at least some of her life. The text was translated by a Benedictine priest, Celestine Kapsner, OSB, who lived at St. John’s Monastery in Collegeville, MN. The introduction to the English text is written by a confrere of Fr. Kapsner, Virgil Michel, OSB ([1935], 2016), who contributed to the liturgical changes which would later become a part of Vatican II (Marx, 1953, p. 1, 6).

Begone, Satan was quickly rather popular, being written about in one of the popular magazines of the era, Time (1935), and being frequently reprinted. Joseph Laycock (2020, pp. 17-32) cites evidence of the pamphlet having a print run of over 10,000 in the first year, and a run of 45,000 in the fourth printing in 1974. Subsequent editions of an earlier translation by Fr. Kapsner of an unrelated anonymous pamphlet on exorcisms, Mary Crushes the Serpent ([1934], 2020), include a new subtitle: A Sequel to Begone, Satan, although there is no mention in the text of the exorcisms done by Fr. Reisinger in Earling.

The Benedictine Fr. Kaspner seems to have an extensive focus on exorcisms in his life. In communication with the archivist of St. John’s Abbey, Br. David Klingman, OSB (2021, no page), all archived materials associated with Fr. Kapsner are related to exorcisms and possessions. The description of the exorcism in Begone, Satan involves many of the key aspects in later representations of cinematic exorcisms: levitation, excessive vomiting, a young woman being strapped to a bed, and rising tension leading to an epic conflict with the exorcist and the demon. The incident is quite famous within writings on North American exorcisms, and is cited in most popular books on the subject, such as by the psychologist Adam Crabtree in Multiple Man (1997 pp. 150-160), hypnotherapist Terrence Palmer in The Science of Spirit Possession(2014, pp. 98-100) and psychiatric professor Richard Gallagher in Demonic Foes (2020, pp. 142-143).

Francis Young argues in A History of Exorcisms in Catholic Christianity (2016, pp. 199-200) that there is a demonstrable textual through line from the Earling pamphlet to the exorcisms performed on the pseudonymous Robbie Manehiem, aka Robbie Doe, in Washington State and St Louis. Notes from both of these events became the inspiration for the novel The Exorcist by William Peter Blatty (1971, pp. 1-340) and the incredibly popular film of the same title in 1973 (Freidkin) as cited in the work of Laycock (2020, pp. 17-32). A feedback loop appears to be in effect; the printing of Begone, Satan that I have (2016) includes multiple pictures, mostly cinematic stills (including, humorously, an uncredited photo of an “exorcist” who is the actor Anthony Hopkins from the film The Rite (Håfstrӧm, 2011).

It is notable that Anna Ecklund has a very limited role in the ceremony, with almost no words being spoken in her voice. From biographical data collected from an unpublished manuscript commented on by Laycock (2020) and published in a collection of primary sources (Bunsee [1934], 2020), it would appear that Ecklund had visited a psychic before possession (Laycock, 2020, p. 26), and had either been pressured into incest by her father (Vogl, 1935, 2016, p. 19) or experienced pressure into a sexual relationship with a boyfriend (Laycock, 2020, p. 25) and had a forced operation, which Laycock (2020, pp. 25-26) speculates as being either an abortion or clitoridectomy, although Vogl (1935, 2020, p. 35) makes pains to indicate Ecklund remained a lifelong virgin. Nancy Caciola’s scholarship of misogyny among medieval exorcisms as shown in her Discerning Spirits (2003, p. 31-320) is worth pointing out as an example of historic uses of exorcisms to reinforce gender norms including chastity, which Vogl ([1935], 2016is at pains to emphasize.

Anna Ecklund is not a free agent, her possession itself is believed by those involved to stem from a curse (“placed a spell on some herbs”, Vogl [1935], 2016, p. 51) by her aunt who is engaged in an illicit romance with her father. The reasoning behind this curse in the Vogl text is that the father has been rebuffed and frustrated in seeking incestuous sexual relations with Anna. Nina, the aunt, is the only female possessing spirits; all others (the father, Judas Iscariot, Beelzebub and Lucifer, seemingly in the text as different demons) are male. The exorcist team consists of the traveling Capuchin Fr. Riesinger and the parish priest Rev. Joseph Steiger, with occasional help from unnamed religious sisters whose convent is invaded with grudging obedience for the event (Vogl, 1935, 2016, pp. 3-4).

Michael Cuneo (2001) has claimed the contemporary popularity of exorcism narratives helps provide a counter-narrative of the heroic priest in a world that is seen both as increasingly secular and often hostile to organized religion. While some traces of the heroic exorcist are seen in Begone, Satan, the vast majority of the focus is on the impact the exorcism has upon the parish priest in Ealing, IA, who was hosting the event. The text attempts to present the suffering of the parish priest as an opportunity for spiritual growth and the exorcist as brave and effective, although the end of the text does admit that earlier and later exorcisms with Riesinger and Anna Ecklund occurred. Laycock (2020), in examining the unpublished manuscript written by Bunsee ([1934], 2020), indicates that exorcisms by Fr. Resinger on Anna Ecklund both predate Begone, Satan and continued long after the pamphlet was completed, even though Vogl makes it appear that the exorcism was (mostly) successful.

For Young (2016, p. 202), these texts develop the themes found throughout North American exorcisms, particularly a sense of the devil fighting both the institutional church and existing power system. As is quoted from one of the devils:

“No, I cannot harm God directly. But I can touch you and His Church… Do you not know the history of Mexico? We have prepared a nice mess for him there.” (Vogl, [1935], 2016, p. 42)

The Mexican Revolution had begun in 1910, and by 1917 a constitution limiting the power of the Catholic Church had been instituted. This led to a regional conflict known as the Cristero War which was occurring during the time of the Earling exorcism (see Butler, 2004, pp. 1-272). A later online recounting of the Earling Exorcism by Pearl, (no date, no page)] , which unfortunately is without any citations, connects the exorcism and secrets revealed by the demons to an incident when the Pope was able to avoid injury in a bombing attack at the Vatican, although this is not mentioned in Vogl ([1935], 2016) or Bunsee ([1934] 2020) texts. However, Bunsee ([1934] 2020) does connect Ecklund’s possession to the supposed rise of the Antichrist between 1952–1955, and the response of a Catholic monarch to help bring about Christ’s peace. One of the devils is quoted by Vogl as saying, “This is the last century. When people will write the year 2000 the end will be at hand” (Vogl [1935] 2016, p. 44).

A sense of apocalypticism runs throughout both the Vogl ([1935] 2016) and Bunsee ([1934] 2020) texts, undoubtedly fueled by the perception of disorder including the above-mentioned conflicts to the south in Mexico as well as to massive social transformation which had occurred in the US. Laycock (2020, p. 31) identifies the loss of the first US Catholic to run for President as a source, although other recent changes in US culture include the completion of World War (1918), women gaining the vote (1920), a terrible global pandemic (1918), alcohol prohibition (1920), and ongoing technological transformation including radio, film, and automobiles. There is a gap of 6-7 years from the exorcism to the composition of both the Bunsee ([1934] 2020) and Vogl ([1935] 2016) texts, during which the Great Depression had begun, resulting in government interventions such as rural electrification, often seen as a rise in socialism, to which the exorcist Reisinger had a particular opposition (Laycock, 2020, p. 27). Certainly, power had shifted from local to national under the 4-term presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt. David Frankfurter (2006) states

“…the very erosion of the local world as a real social entity capable of maintaining traditions for the resolution of misfortune indeed, an anxious tendency to frame every misfortune or deviant behavior in global terms– led communities to seek ever new totalizing frameworks for local crises” (p. 8).

In the Vogl text (1935, 2016, pp. 42-44) the Antichrist is expected to either have already been born or was shortly expected in Palestine. References to the apocryphal vision of Pope Leo XIII are mentioned several times in the Vogl text (1935, 2016, p.2, pp. 24-25). This vision, in which the Pope overheard the Devil and God allowing demonic influence in the church for up to 100 years, leading to him penning the Prayer to St Michael, has remained a common story among the more conservative branches of the Catholic Church, although there are no contemporary accounts and the later stories about the incident tend to be contradictory (Demers, 2018). Gallagher (2020, p. 34) points to the clearly unfulfilled nature of this prophecy by Anna Ecklund or her possessing demons as proof of the lying nature of the demonic spirits, although it is clear in Begone, Satan (Vogl [1935] 2016) that the author fully believes in the prophecy. Laycock offers evidence that confreres of Fr. Resinger thought him too focused on apocalyptic thinking and exorcisms in general, which is one reason he had frequent re-assignments (2020, p. 24, p. 27).

Concern about theological orthodoxy is found throughout modern exorcism stories. In Virgil Michel’s introduction to the Vogl text ([1935] 2016), we see him contrast the beliefs of Catholics with Protestants, especially related to the exorcism associated with baptism. Bunsee ([1935] 2020) mentions that as a youth, Ecklund had challenges working in a factory with Protestant co-workers and had visited with a psychic. The possessing spirit of her cursing aunt is identified as a Lutheran. Contemporary examples in exorcism narratives include the psychiatrist Richard Gallagher (2020), whose possessed patients have been supposedly opened to demonic forces by satanic, occult, or Hindu practices, which is also seen in M. Scott Peck’s Glimpse of the Devil (2005), where his possessed patients’ spiritual explorations are seen by Peck as the explanation for their possessed states. There may also be concern about political orthodoxy, Laycock (2020, p. 27) has found evidence that Fr. Resineger had attended courses to learn how to counteract Socialism, a party that in the US presidential elections had won close to a million votes in both 1912 and 1920 (Dray, 2010, p. 228).

Young (2016, p. 2) argues that exorcism narratives increase when the church is facing internal and external challenges. While most modern proponents of exorcism seem to be theologically conservative, such as Peck (2005) and Gallagher (2020), the evidence in Begone, Satan (Vogl [1935] 2016) appears to be slightly more nuanced. For example, the introduction is written by a liturgical reformer whose obituary is published in The Catholic Worker, a movement associated with the Catholic left, and later promotions of exorcisms have occurred under the Papacies of Benedict XVI – who had been seen as rolling back some of the Vatican II reforms – as well as Francis I – who has been seen as advancing a Vatican II agenda (Catholic News Services, 2020). While it is possible Young (2016, p. 2) is overstating the case of intra-church conflict, undoubtedly the sense of ‘the church vs. the world’ is a through-line beginning at least with Leo XIII (who famously did not leave the Vatican grounds during his papacy in order to deny the validity of the newly unified Italian state (Young, 2006, pp. 2-3, p. 181) and continuing into the Papacy of Francis, who is quoted as claiming that the most serious challenge of his Pontificate was not the sex abuse scandal, a divided church, or the loss of faithful, but is “the masonic lobby” (Chapman, 2013).

Fear of plotting Masons is nothing new within the church. Leo XIII, proponent of exorcisms and possible seer, had significant concerns about Masons. His encyclical Humanen genus (1884) includes rejection of Masonic activity due to not only the secrecy of the organization, but also the promotion of public schooling, the popular vote, and naturalism. Frankfurter (2006) argues that a totalizing logic, whereby individual and specific anxieties are universalized and projected, carries significant danger for oppressed members of minorities:

“What produces panics and mass-purges, then, is thinking about familiar anxieties – witches, foreigners, immorality, even economic inequality- in newly rarified terms, and especially (although not exclusively) in the radically polarized Christian terms of Satanic evil.” (pps. 7-8)

The Southern Poverty Law Center notes that conspiratorial thoughts about Freemasons frequently bleeds into anti-Semitic thinking (Beirich, no date, no page ). In the writing of his Encyclical, Pope Leo connects the territorial losses suffered by the Papal States, as well as a sense of loss over centuries after the Reformation, and projects blame onto a worldwide fraternal organization which is then connected to an unseen cabal of Jews (Young, 2016, pp. 191-192). This is hardly unique to Roman Catholicism, and in fact we will see a similar process (fear of an international conspiracy amid a sense of loss of power, often believed due to the hidden power of Jews), predominant among Q supporters (Rothschild, 2021, p. 31, pp. 49-55).

Historical Precedents

Titus Livy’s only surviving text, often known as “History of Rome” but originally entitled Ab Urbe Condita, or “From the Founding of the City”, was written at the end of the reign of Caesar Augustus and was completed after Caesar’s death. Therefore, his description of the suppression of the Bacchae or Dionysus Rites, which occurred 200 years beforehand, are held to be somewhat biased and therefore suspect, even if there is no doubt the suppression did occur (Frankfurter, 2016, p. 100). The timeframe of the composition was one of rapid change in political power, with civil wars, the assassination of Julius Caesar, and consolidation of power by Augustus throughout the Empire. Included in Livy’s description of the Bacchus Rites are themes of conspiracy for power coupled with secret cultish practices, for example:

Men, as if insane, with fanatical tossings of their bodies, would utter prophecies. Matrons in the dress of Bacchantes, with disheveled hair and carrying blazing torches, would run down to the Tiber, and plunging their torches in the water (because they contained live sulfur mixed with calcium) would bring them out still burning (Livy39. 13.11-12).

Refusal to join in the ritual could supposedly result in being ritually murdered:

“Men were alleged to have been carried off by the gods who had been bound to a machine and borne away out of sight to hidden caves: they were those who had refused either to conspire or to join in the crimes or to suffer abuse (Livy 39.13.13)

There was concern about the impact of the cult on the functioning of society and of state. One of the concerns was that the number of bacchanalian initiates was very large and powerful. Livy quotes a female witness:

“Their number, she said, was very great, almost constituting a second state; among them were certain men and women of high rank.” (Livy 30.13.14)

Livy appears anxious over the fact the Bacchus cult involved a mixing of sexes and genders, which resulted in the feminization of the men involved:

“First, then, a great part of them are women, and they are the source of this mischief; then there are men very like the women, debauched and debauchers, fanatical, with senses dulled by wakefulness, wine, noise and shouts at night.” (Livy29.15.8).

For Livy, this overturning of sexual norms resulted in further overturning of the social order:

“Yet it would be less serious if their wrongdoing had merely made them effeminate —that was in great measure their personal dishonor —and if they had kept their hands from crime and their thoughts from evil designs: never has there been so much evil in the state nor affecting so many people in so many ways. Whatever villainy there has been in recent years due to lust, whatever to fraud, whatever to crime, I tell you, has arisen from this one cult.” (Livy 39.16.1–2).

Roman authors frequently criticized foreign opponents through accusations of sexual immorality, such as Julius Caesar (who lived a generation before Livy) claiming Celtic people practiced incest, which may have been connected to extended kin networks living together in rural communities (Gillespie, 2018). For Livy, though, the sex and ritual murder seem almost secondary in concern to the threat sexual gender-bending play to the security of the state.

Norman Cohn (1975, p. 9-231) coined the term “nocturnal ritual fantasy” in his classic text Europe’s Inner Demons to describe the ongoing repetition of the themes of the nighttime orgy from the Graeco-Roman era into the medieval era. These nighttime activities include ritual murder, cannibalism, demonic possession and sexual immortality, although he does not mention Livy or the Bacchanalia. Cohn traces these descriptions to activities including the early suppression of Christianity by the Roman State, later suppression of Jewish celebrations after Rome was converted to Christianity, as well as descriptions of the ceremonies of heretics in late Rome and early Medieval Europe and of the Witch Sabbaths in late Medieval and early Modern eras. M.B. Barbezat (2017), in an article on heretical activities in 12th–14th century Europe, expands upon Cohn (1975), noting how there are subtle changes in the reports of nocturnal ritual fantasy. For example, in 12th century reports of heretical rituals, the sexual behavior became less incestuous and involved more same-sex activity.

David Frankfurter (2006, p. 4) cautions that in reading conspiratorial texts we should not assume that any of these reports of ritual murder and sexual deviance reflect actual events; they instead seem to be socially sanctioned psychological projections upon some “Other”, be the person Jew, heretic, witch, or (later) Mason. The logic seems to be that the Other has proven the errors in belief and practice by their immorality (such as lack of keeping in marriage, orgiastic behavior, homosexual behavior, support of social programming), orthopraxy following orthodoxy. Talia Levin (2020)argues such persistence is due in part due to the logical conclusion; if my opponents are not simply wrong but are in fact evil, then crushing them is the only appropriate response.

QAnon and Blood Libel

In a comparison of QAnon with the Motif-Index of Folk Literature (an extensive database of folkloric themes), Deutche and Bochantin (2020) found similarities between stories of child abduction, child sacrifice, and the use of blood or other body parts of children, all of which have a long history in antisemitic tropes from the ancient world through to the Shoah. The authors note that the 3rd Q drop (messages left on online forums, starting with 4chan) referenced extensive government employees worshiping Satan. Modern organized resistance to a secret sexually deviant cabal seeking to undermine the state is a major organizing force in parts of the far-right (Rothschild, 2021, pp. 25-27, p. 41, pp. 123-126).

Before QAnon there was Pizzagate, the report that a Washington D.C. pizza parlor, CometPingPong (which is host to a drag show) was the center of a child sex ring in the basement, although there is no basement in the building (Rothschild, 2021, p. 25-27). Barbezat (2017) notes that the owner, a gay man, was a proud supported of Hillary Clinton; he also once dated a prominent former right-wing activist who later became heretical to the movement. The pizza parlor was targeted by an armed man who live-streamed his attempted liberation of the location (only to find people simply eating pizza). Twitter personalities like Jack Posobiec have consistently promoted Pizzagate and other conspiratorial claims; he also disrupted a net neutrality rally by claiming there is extensive Satanic ritual pornography available online (Collins, 2017, no page).

Attacks on public buildings have been increasingly a strategy of the far right, including the far-right attack on Germany’s Reichstag (Sauerbrey, 2020, no page) and the US Capital in 2021. Some of the attendees of the Capital riot were overtly religious with formal denominational ties, such as the Catholic priest who attempted to exorcize the demon Baphomet from the Capital (Salcado, 2021). Baphomet was the reported idol of the Knights Templar, whose homosexual activities were supposedly a reason for their suppression (Stahulajak, 2013, 71-82). Baphomet has now been embraced by the Temple of Satan due to its androgenous presentation (Rose, 2021).

Other attendees of the Capital attack seem to be engaging in a bricolage, such as the Healing Church of Rhode Island, who wear colonial era tri-cornered hats, images of the Virgin of Guadalupe (the patron of Mexico), and blow cannabis through shofars (NBC 10 News, 2016). The theological mix, with a lack of clear denominational lines and coherent theology, appears to be increasingly common. Boorstein (2021) notes that among those who attended the January 6 riot and attempted coup, many had limited knowledge of their reported beliefs, even if they were religiously motivated by their extreme behavior. David French (2021) claims that among far-right US supporters, identification with evangelical identity has been increasing, while actual affirmation of evangelical belief and church attendance is very low. Steven Prothero (2009) has noted in general low religious literacy within the US, making conspiratorial and antisemitic thinking easier to spread. In O’Donnell’s (2020a, 2020b) research, belief in possession narratives on a national level, requiring large scale “spiritual warfare” is seen among the so called “neo-conservative” movement, a third wave which is often nondenominational in formal affiliation.

Surely no-one is more often portrayed or used as visual shorthand for the movement than the QAnon Shaman, Jake Angeli (aka Jake Chansley). Angeli believes not only that there were reasons to oppose the counting of the electoral ballots that was disrupted by the Capitol attack; he has also stated that Washington DC is built on “ley lines” and was designed and run by a secret cabal of Freemasons (Kunkle, 2021). He was clearly joined by many who at least share some of his beliefs, although it should be noted that he has been diagnosed by a prison evaluation to have transient schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression and anxiety (Lynch, 2021).

In a review by M.R. Royce (2021) of the self-published One Mind at a Time by Angeli (2020), it is noted that the text lacks any racist or anti-Semitic content and reads more left-libertarian than right-fascist. However, the text does claim there are multiple and interlocking layers of deep state conspiracy in the US Government (and the Holy See) that involve child sex trafficking. Royce states:

“The word that for this reviewer most fully encapsulates Chansley’s manifesto is alienation, the state of being artificially cut off from the natural society of one’s fellow creatures. The Capitol Hill putschists of the sixth of January deliberately threw the gauntlet down and issued an existential challenge to American democracy, a rebellion that requires an existential answer.” (Royce, 2021).

The groundwork for the January 6th attack was laid well before. Alex Jones, a media personality and early promoter of the QAnon conspiracy, had long been claiming that members of the Democratic party’s leadership were literal demon possessed or demons themselves. In commenting on Donald Trump’s presidential opponent in 2016, Hillary Clinton, Jones had stated:

“She is an abject, psychopathic, demon from hell that as soon as she gets into power is going to try and destroy the planet…she’s so dark now, and so evil, and so possessed that they are having nightmares…I was told by people around her that they think she is demon possessed” (quoted in Klein, 2016, no page).

Jones, in his diatribe, also claims that Trump’s presidential predecessor, Barak Obama, is also demonically possessed:

“You can’t wash that evil off, man… Obama and Hilary both smell like sulfur…they’re scared of her. And they say she is a frickin’ demon and she stinks and so does Obama. I go, like what? Sulfur. They smell like hell” (quoted in Klein, 2016, no page).

S. Jonathan O’Donnell (2020a) has studied the rise of Christian Nationalism, a belief system that holds that laws are valid only when they correspond to a specific Biblical understanding. The present state systems are viewed as overtly demonic and supported by people who are possessed by demons. The proper response to this situation is spiritual warfare, which at times spills over into real violence, a situation at least some at the January 6 attack were overt in claiming. Blaikie (2021) notes that the rise of Christian nationalism in general, and QAnon theories in particular, occurred in the midst of the fraying of the bonds of unions, manufacturing (as jobs went overseas), and other forms of connection, particularly among the working classes, which Donald Trump as president was able to galvanize. As Frankfurter noted, “That is, the real atrocities of history seem to take place not in the perverse ceremonies of some evil cult but rather in the course of purging such cults from the world.” (2016, p.12).

As a mental health provider, I have seen the ongoing experience of alienation and fraying social bonds compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic. It is amid these experiences that faith communities which encourage clear boundaries and demonize opponents become very appealing. Within my hometown, one such Catholic cleric, Fr Altman, has recently been removed from his pulpit ministry after stating in regard to the COVID-19 vaccine that it is:

“diabolical for anyone to virtue-signal/shame/compel you to take such an experimental drug, making you nothing other than a guinea pig… God is still the best doctor and prayer is still the best medicine” (Henken, 2021, no page).

Conspiracies are of course by no means exclusive to the political right or to the religious. The left-wing anti-vaccination movement has shown significant overlap with right wing conspiratorial thinking; and language from the left is intentionally repurposed for exactly that reason (Monbiot, 2021).

What is to be done? There seems to be a political and economic space for rebuilding frayed connections, such as laws that assist in making labor organizing easier. For those who are educators, it is sobering to see that conspiratorial thinking is connected to lower skills in critical thought (Elder, 2021). Emphasizing vigorous analysis and deep thinking, in our classrooms, in our families, in our communities; all can have a beneficial impact. The appeal of the conspiracy is that it makes the randomness of the universe, the absurdity of existence, seem to make sense, and casts us as the knower of secrets into a role that is special and unique. Professor Mark Lorch (2017, no page) encourages not the sharing of counterfactuals but instead the engagement in serious albeit friendly questions. Hard work indeed, especially when the theories are hateful.

Creative engagement with the conspiracy theory, subverting and playing with the themes, may be the most engaging. The Italian author Umberto Eco frequently played with conspiratorial thought for dramatic effect, including Foucault’s Pendulum (tran. 1989) where a computer program crunches conspiracy theory and somehow creates a threat, or Prague Cemetery (trans. 2011) which explores the creation of the anti-Semitic forgery The Protocols of the Elders of Zion as well as the appeal of satanic imagery in fin de siècle France. Perhaps no-one has better capitalized on the perceived connection of Satan and homosexuality than Lil Nas X. Olla (2021) notes how the rapper has combined expressions of his queerness with satanic imagery in both a limited-edition sneaker (with trace amounts of human blood) and in his video “Montero: Call Me by My Name” (Lil Nas X, 2020, no page), in which he encounters a serpent in the Garden of Eden and then descends into Hell to perform a lap dance for the Devil, whom he then usurps. For the artist, creative play at the boundaries becomes coupled with capitalistic opportunity. Perhaps ongoing creative play is the best response to the literal demonization of political opponents, although it risks feeding into existing narratives.

CONCLUSION

From classical sources outlying worries of an external foreign religion that constitutes a second state including a reversal of gender roles, through to modern day political activities, a deep anxiety about conspiratorial thinking has continued. Demonization, both figuratively and literal, coupled with a belief in possession appears to be a common theme in at least some conspiracies, including the currently popular QAnon as well as older fears of the effects of revolutions and the threat of socialism. Economic and social disruption do appear to be contributing factors to the rise in demonic and conspiratorial interpretations of power, as does an emphasis on sexual purity and strict gender roles. Some creative responses, such as in the novels of Umberto Eco and the rap lyrics and music videos of Lil Nas X, have played with these themes with a joyous outcome. Ongoing creative exploration in this area seems fruitful, as does the difficult work of engaging with those who continue to think in conspiratorial terms.

References

Angeli, J. (2020). One mind at a time: A deep state of illusion. Independently published (June 18, 2020).

Barbezat, M. (2017). “Pizzagate and the nocturnal ritual fantasy: Imaginary cults, fake news, and real violence. The Public Medievalist, May 4, 2017. Retrieved from: https://www.publicmedievalist.com/pizzagate-cults/ on September 10, 2021

Beirich, H. (N.D.). “Catholics and conspiracies.” Southern Poverty Law Center website, retrieved from: https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/intelligence-report/2015/catholics-and-conspiracies on August 4, 2021.

Blaikie, B. (2021). “Tracing the toxic roots of the capital attack.” The Rabble, January 26, 2021. Retrieved from: https://rabble.ca/columnists/2021/01/tracing-toxic-roots-capitol-attack?fbclid=IwAR30mxSWn7rf001dOj1HF_s2OK2ls6acdGtEWNLgnkWfB_s_PTLSwZ1Eyew on September 18, 2021.

Blatty, W.P. (1971). The exorcist. New York: Harper.

Boorstein, M. (2021). “A horn wearing ‘shaman’. A cowboy evangelist. For some, the Capital attack was a kind of Christian revolt.” The Washington Post, July 6, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/religion/2021/07/06/capitol-insurrection-trump-christian-nationalism-shaman/ on September 18, 2021.

Bunsee, F.J. (2020). “The Earling possession case, 1934.” In The Penguin book of exorcisms, ed. Laycock, J.P..pp. 234-244. New York: Penguin.

Butler, Butler, Matthew. Popular Piety and political identity in Mexico’s Cristero Rebellion: Michoacán, 1927–29. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Cacialo, N. (2003). Discerning spirits: Divine and demonic possession in the middle ages. Ithaca: Cornell University Press

Catholic News Services. (2020). “Exorcisms and the popes: Stories from inside the Vatican. Retrieved from https://catholicsentinel.org/Content/News/Pope-Francis-and-Vatican/Article/Exorcisms-and-the-popes-Stories-from-inside-the-Vatican-/2/61/41212 on March 6, 2021.

Chapman, M.W. (2015). “Pope Francis: ‘Masonic lobbies…this is the most serious problem for me.’” CNSN News, August 2, 2015. Retrieved from: https://cnsnews.com/news/article/pope-francis-masonic-lobbies-most-serious-problem-me on August 4, 2021.

Cohn, N. (1975). Europe’s inner demons: The demonization of Christians in medieval Europe. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Collins, B. (2017). “Alt-right claims net neutrality promotes ‘satanic porn’ in planted flyers. The Daily Beast, July 12, 2017. Retrieved from: https://www.thedailybeast.com/notorious-pizzagate-truther-plants-fake-net-neutrality-flyers-backing-satanic-porn on September 10, 2021.

Crabtree, A. (1997). Multiple man: Explorations in possession and multiple personality. Ontario: Somerville House

Cuneo, M. (2001). American exorcist: Expelling demons in the land of plenty. New York: Doubleday.

Demers, D. (2018). “God’s chat with the devil: The vision of Pope Leo XIII.” Catholic Stand, 17 May 2018. Retrieved from: https://catholicstand.com/gods-chat-devil-popeleo/ on August 4, 2021.

Deutche, J. & Bochatin, L. (2020). “The folkloric roots of the QAnon conspiracy.” Folklife, December 7, 2020. Retrieved from: https://folklife.si.edu/magazine/folkloric-roots-of-qanon-conspiracy on September 16, 2021.

Dray, P. (2010). There is power in a union: The epic story of labor in America. New York: Anchor.

Elder, J. (2021). “Conspiracy theories lack critical thinking skills: New study.” The New Daily, July 25, 2021. Retrieved from: https://thenewdaily.com.au/life/science/2021/07/25/conspiracy-theorists-lack-critical-thinking/?fbclid=IwAR0MdauFG32fLD02adAG-kqBW6LMVIyfGRkDrSwEPOoPn4FgQBjHuFSSg10 on September 26, 2021.

Frankfurter, D. (2006). Evil incarnate: Rumors of demonic conspiracy and satanic abuse in history. Princeton, NJ; Princeton University Press.

Freidkin, W. (1973). The exorcist. [Motion Picture.] Warner Bros.

French, D. (2021). “Did Donald Trump make the church great again?” The Dispatch, September 19, 2021. Retrieved from: https://frenchpress.thedispatch.com/p/did-donald-trump-make-the-church on September 25, 2021.

Gallagher, R. (2020). Demonic foes: My twenty-five years as a psychiatrist investigating possessions, diabolic attacks, and the paranormal. New York: Chaperone.

Gillespie, C.T. (2018). Boudica: Warrior woman of Roman Britain. Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press.

Gilly, A. (2006). The Mexican revolution: A people’s history. New York: The New Press.

Håfstrӧm, M. (director). (2011). The rite. [Film]. New Line.

Henken, O. (2021). “Father Altman under fire for COVID protocols, vaccine misinformation.” La Crosse Tribune, April 25, 2021. Retrieved from: https://lacrossetribune.com/news/local/father-altman-under-fire-for-covid-protocols-vaccine-misinformation/article_278faaa0-6815-58a7-9ab3-d31a1c5da4a4.html September 25, 2021.

Kapsner, C. (1934, 2020) [trans]. Mary crushes the serpent: 30 years experiences of an exorcist told in his own words. A sequel to Begone Satan. Lake Elmo, MN: Keef’s Catholic Gift Shop.

Klein, E. (October 10, 2016). “Trump ally Alex Jones thinks Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton are literally demons from hell. Vox. Retrieved from: https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2016/10/10/13233338/alex-jones-trump-clinton-demon on August 13, 2022.

Klingman, D. (2021). Personal communication with the author. August 13, 2021.

Kunkle, Fredrick (January 9, 2021). “Trump supporter in horns and fur is charged in Capital riot.” Washington Post. Retrieved from: https://web.archive.org/web/20210111054231/https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/jacob-chansely-horn-qanon-capitol-riot/2021/01/09/5d3c2c96-52b9-11eb-bda4-615aaefd0555_story.html January 12, 2021.

Laycock, J. (2020). “The secret history of ‘The Earling Exorcism’”. In The social scientific study of exorcisms in Christianity, Eds G. Gordon & A. Possamai, pp. 17-32. Cham, Switzerland: Springer

Leo XIII. (1884). The letter Humanum genus of the Pope Leo XIII and the response by General Albert Pike, Supreme commander of the Scottish Rite of Freemasonry, Southern District, USA. Retrieved from: https://books.google.com/books?id=NYTOAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false on August 4, 2021.

Levin, T. (2020). “Qanon, blood libel, and the satanic panic: How the ancient, antisemetic nocturnal ritual fantasy expresses itself through the ages- and explains the right’s fascination with fringe conspiracy theories. The New Republic, Retrieved from https://newrepublic.com/article/159529/qanon-blood-libel-satanic-panic on March 6, 2022.

Lil Nas X. (2021). “Montero: Call me by your name.” Video. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4bmfHuzJqMA on March 6, 2021.

Livy. (1936). History of Rome: Books XXXVIII-XXXIX with an English Translation, E.T. Sage,. Cambridge. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press. Retrieved from: http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0166%3Abook%3D38 on March 5, 2022.

Lorch, M. (2017). “Why people believe in conspiracy theories-and how to change their minds.” The Conversation, August 17, 2017. Retrieved from: https://theconversation.com/why-people-believe-in-conspiracy-theories-and-how-to-change-their-minds-82514 on September 26, 2021.

Lynch, S.N. (2021). “QAnon Shaman in plea negotiations after mental health diagnoses.” Reuters. July 26, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.reuters.com/world/us/exclusive-qanon-shaman-plea-negotiations-after-mental-health-diagnosis-lawyer-2021-07-23/ on September 18, 2021.

Marx, P. (1953). “Dom Virgil Michel.” The Catholic Worker, XX, Vol. 4, 1 November 1953.

Monbiot, G. (2021). “It’s shocking to see so many leftwingers lured to the far-right by conspiracy theories.” The Guardian, September 22, 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/sep/22/leftwingers-far-right-conspiracy-theories-anti-vaxxers-power on September 26, 2021.

NBC 10 News (2016). “Members of Rhode Island cannabis church arrested on marijuana charges.” Retrieved from https://turnto10.com/news/local/members-of-rhode-island-cannabis-church-arrested-on-marijuana-charges on March 6, 2022

O’Donnell, S.J. (2020a). “The deliverance of the administrative state: Deep state conspiracy, charismatic demonology, and the post-truth politics of American Christian nationalism. Religion, 50, 2020, 4. Retrieved from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0048721X.2020.1810817?journalCode=rrel20 on September 25, 2021.

O’Donnell, S.J. (2020b). Passing orders: Demonology and sovereignty in American spiritual warfare. New York: Fordham University Press.

Olla, A. (2021). “Satan shoes? Sure. But Little Nas X is not leading American kids to devil-worship. The Guardian, 1 April 2021. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/apr/01/satan-shoes-sure-but-lil-nas-x-is-not-leading-american-kids-to-devil-worship on April 22, 2021.

Palmer, T. (2014). The science of spirit possession (2nd Ed.) Newcastle-upon-tyne: Cambridge Scholars Press:

Pearl, M. (ND). “The exorcism of Emma: An untold true story.” Truly+Adventurous. Retrieved on from: https://www.trulyadventure.us/exorcisms-of-emma August 12, 2021.

Peck, M.S. (2005). Glimpses of the devil: A psychiatrist’s personal accounts of possession. New York: Free Press.

Prothero, S. (2009). Religious literacy: What every American needs to know–and doesn’t. New York: HarperOne.

Rose, A. (2021). “Sex work and satanism.” Blessed are the binary breakers. Retrieved from: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1gpKj9-f84qA4C5wnlHdpaynZ_OACy5-uBP7Xb9mRMOc/edit on September 9, 2021.

Rothschild, M. (2021). The storm is upon us: How QAnon became a movement, cult, and conspiracy theory of everything. Brooklyn, NY: Melville

Royce, M.R. (2021). “Edge of darkness: A review of Jacob Angeli’s One Mind at a time: A deep state of illusion. Providence Magazine, February 1, 2021. Retrieved from: https://providencemag.com/2021/02/edge-darkness-review-jacob-angeli-one-mind-time-deep-state-illusion/ on September 9, 2021.

Salcado, A. (2021). “A Catholic priest at Trump’s Jan. 6 rally said he performed an exorcism on Congress. He’s not an exorcist, the church said.” Washington Post, Feb 4, 20201. Retrieved from: https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2021/02/04/nebraska-priest-excorcism-capitol-rally/ on September 9, 2021.

Sauerbrey, A. (2020). “Far-right protestors stormed Germany’s parliament: What can America Learn?” New York Times, January 8, 2021, Retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/08/opinion/germany-parliament-us-capitol.html on March 6, 2022.

Stahulajak, Z. (2013). Pornographic archaeology: Medicine, medievalism, and the invention of the French nation. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Time (1935). “Religion: Exorcist and energumen.” Time, Monday, February 17, 1936. Retrieved from: https://archive.ph/20120912074339/http://www.time.com/time/printout/0,8816,883526,00.html on August 8, 2021.

Vogl, Carl (1935, 2016). Begone, Satan. Translated by Rev. Celestine Kapsner, O.S.B. Las Vegas: Drumbeats Media.

Young, F. (2016). A history of exorcisms in Catholic Christianity. New York: Palgrave.

-

Here is the JEEP article: “Demons on the Couch”.

This ended up growing into the book. If you want the book, let me know. The list price is ridiculous!

-

Here is my old article from JEEP (Journal of Exceptional Experiences in Psychology), a great journal which has since gone dark. Link here:

-

Thanks for visiting the site. I hope to post some of my writings here.

-

Subscribe

Subscribed

Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.